Any merit to bicameralism is defeated by our budget system

Constant wrangling over continuing resolutions creates more, not fewer, opportunities for ill advised changes

With the American government emerging from its longest shut down in history, and with the current budget lasting only a few months, more light than ever has been shown on the American system of budgeting and the American legislature in general. The strange situation we find ourselves in, where even a majority party with a 'trifecta' control of the House, Senate, and White House cannot properly fund the government, maybe benefit the Democratic party and liberalism at some juncture in the current congress (though little was accomplished in the most recent round of budget wrangling); however, the peculiarities that make this such a common problem in US governance persist without any real logic to them, and a longer term solution - ideally, when Democrats again control congress - is desirable.

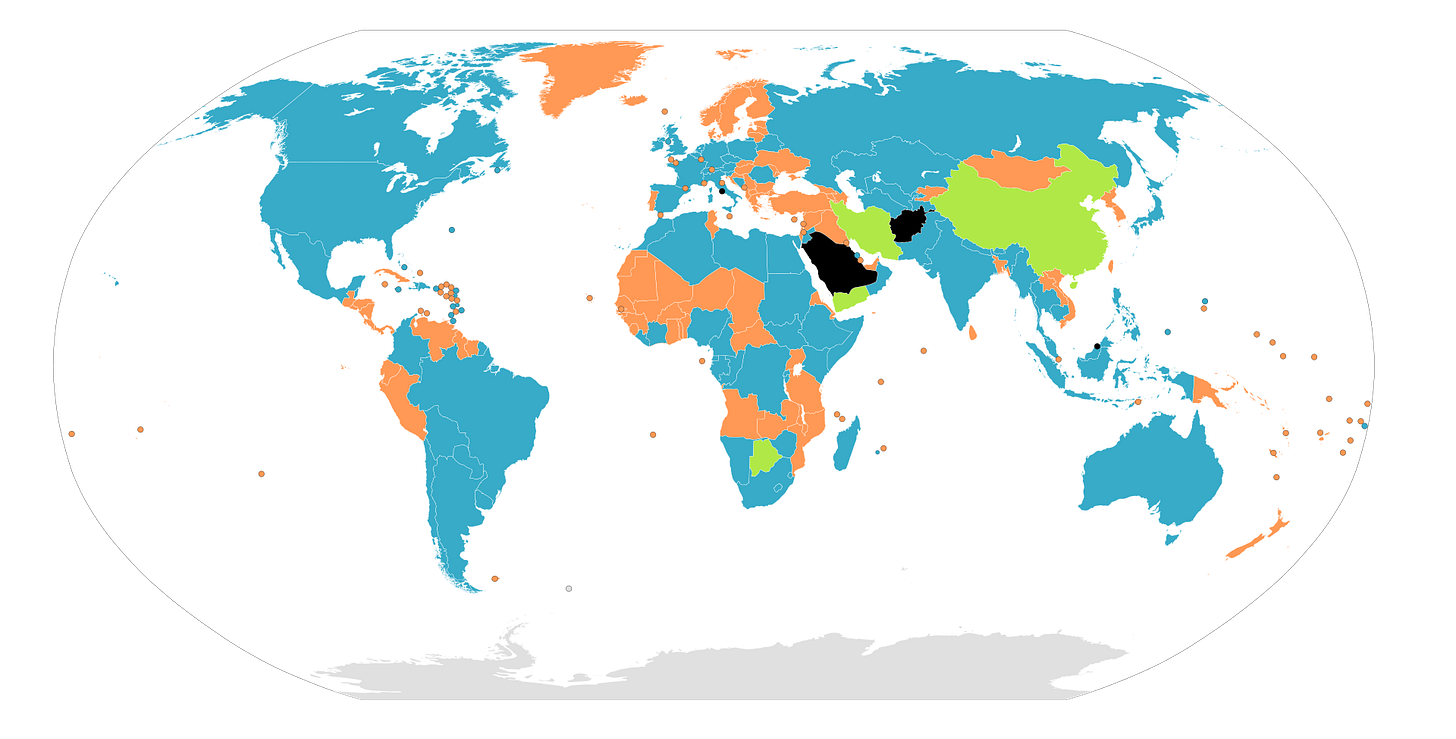

‘American exceptionalism’ is a phrase with many meanings, but among the ways in which the United States truly is unique is in its constitution - with a mix of federalism, separation of executive and legislative power, and institution of a bicameral legislature, the American constitution was truly an oddity when it was created, and few if any countries have imitated all of its features precisely. While many Americans remain exceedingly proud of their system, with a degree of near-religious devotion to its framers, most subsequent constitutions, even those inspired to some extent by the American revolution, have chosen not to imitate many of its features. Many jettison the bicameral nature of the legislative branch, or (as in the United Kingdom) have limited its practical function. It was, after all, born of a very particular dispute between large and small states that existed around American independence, but which was not replicated in many of the democracies that were founded subsequently:

However, roughly half of states with an elected legislature do embrace bicameralism, at least to some extent. This is true even of more unitary democracies, like France or Chile, where there is not a recognized role for ‘states’ as sovereigns. What purpose could his serve?

One answer can be found in Madison’s Federalist Paper 62. In addition to explaining how bicameralism allows for a balancing of large and small states, and thus was a compromise necessary for getting approval of the constitution in the first place, Madison offers another argument in its favor, claiming that

“Another advantage accruing from this ingredient in the constitution of the senate, is the additional impediment it must prove against improper acts of legislation. No law or resolution can now be passed without the concurrence first of a majority of the people, and then of a majority of the states….The necessity of a senate is not less indicated by the propensity of all single and numerous assemblies, to yield to the impulse of sudden and violent passions, and to be seduced by factious leaders, into intemperate and pernicious resolutions.”

The goal, then, would be a sort of salutary conservatism, wherein requiring consent of both the House and the Senate for legislation would blunt any ‘impulsive’ legislative tendencies. Absent agreement from both chambers, the status quo would generally continue - a situation the framers generally considered superior to frequent changes in the law.

However, in the current system of the US Federal budget, this ostensible strength of the two-chamber system is turned on its head. As things stand, the consent of both ‘the people’ and ‘the states’ must be gained simply to maintain a status quo of funding. This situation is not one anticipated directly in the constitution, and indeed it was not until the 1980s, based on the opinion of Jimmy Carter’s Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti, that the government acted on the assumption that it needed to shut itself down - as opposed to simply continue the status quo of operations - if Congress failed to legislate new spending.

Whatever the legal merits of the opinion given the legislation at the time, it is obvious that it undermines the very reasoning behind a bicameral system. In the case of a divided congress, or even one where one chamber cannot maintain a functional majority despite a partisan one (as for example in the US Senate today), it creates myriad openings for ‘improper acts of legislation’, and puts the rest of the legislative branch in the position of either accepting the demands of potential hold outs or halting the government from doing any work at all. It is extremely doubtful that congress adequately representing ‘the majority of the people and of the states’ would change the law, as it Congress felt compelled to do in 2024, to outlaw the flying of pride flags on US Embassies - indeed that is precisely the sort of petty and obviously factious policy that the Senate is intended to check, per Madison’s reasoning. However, given the current procedure regarding budget approvals and government shutdowns, the Senate is effectively blocked from serving this role unless Senators are willing to take the even more disruptive course of shutting down the entire government. If the thrust of the bicameral system was that the House could not be trusted to, on its own, change the law, surely it cannot be trusted to, on its own, shut down the entirety of government.

The situation observed in 2025 was even more absurd, in some ways - there, a minority of the Senate attempted to force concessions from the party that had a majority in both chambers. Of course, the demanded concessions were themselves more reasonable: an extension of Affordable Care Act subsidies that had been operating for several years. However, on principle the ability of 41 Senators to force a government shut down if their demands are not met is a tremendous vulnerability of the system - and if the parties were reversed, it's entirely that those 40 Senators may represent a third or less of the US population.

One solution to this problem - and many others of government gridlock - is to adopt a system more like the Westminster one, where one chamber can effectively run the legislative agenda on important matters. However, few elements of the constitution are more difficult to imagine seriously changing than its bicameral nature - after all, by any constitutional path, it would require a supermajority of one chamber voting away a substantial portion of their powers. By and large we are stuck with the system we have.

A less ambitious solution is possibly, however - use legislation to reverse Civiletti’s legal opinion by explicitly authorizing government agencies to operate at their status quo levels until a change in funding is authorized by congress - as well effectively the case until 1980. In any event, the continued operation of some government functions but not others renders whatever logic the 'shut down' theater largely null. Another step would be eliminating or at least changing the function of the Anti-Deficiency Act (as well as eliminating ‘debt ceiling’ provisions) to prevent the extreme funding cliffs that loom over the course of proper legislative negotiation as intended by the framers of the constitution. This most clearly works to the advantage of Democrats, since their constituencies are most directly harmed by government shutdowns in most cases. However, Republicans may also see a benefit - especially if every continuing resolution sparks a motion to vacate the Speaker’s chair, leaving the entire caucus at the mercy of its most ridiculous members.

These are not, explicitly, the kind of promises that win elections, but they should be part of the Democrats' agenda the next time they retake control of congress. Doing so is good policy, but also good politics. It will improve the functioning of the legislative branch to be something at least somewhat more akin to what Madison describes, and would remove an enormous headache from Americans sick of watching legislative dysfunction effectively crash the Federal government, delivering the kind of governing stability that Americans are likely to appreciate after a few more years of Trump-induced turbulence.