Birthright Citizenship is Still Settled

As President Trump takes office for the second time, all indications are that he will attempt to interpret the US constitution to deny citizenship to children born in the US on the basis of their parents' relationship to the Federal Government. While this is a substantial break with US law, it is well in line with the traditions of older European absolute monarchies and is still the practice in much of the old world. The divide between jus soli (based on the soil - citizenship by birth on the land of a country) and jus sanguinis (based on blood - citizenship by biological descent from a citizen) is an old one - in general, the former is common in the Americas, while the latter prevails in most of the rest of the world. But in the United States, the issue has been decided by a clear reading of the 14th Amendment, and defended by our liberal tradition. Jus soli is the best path forward for a liberal state and, despite what Donald Trump might tell you, is the only path forward under the US Constitution.

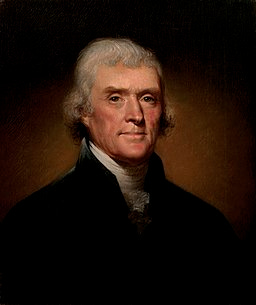

The question of restricting immigration is one of the oldest in American history - predating, in fact, independence. The Declaration of Independence lists among the sins of King George the fact that “He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither”. The colonial leaders pushing for revolution understood that a growing and dynamic population was critical to the long-term security and self-sufficiency of the country they hoped to build. Naturalization authority was placed specifically with Congress with the ratification of the constitution, and the question of naturalization was frequently a controversial one - never more so than with the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

The Constitution left Congress with broad authority to set the naturalization rules it saw fit, providing no guidance on naturalization or on citizenship until the 1867 passage of the 14th Amendment. Congress periodically revised its Naturalization laws but generally maintained the broad strokes - immigrants had to be free white people and needed to reside in the country for a set number of years before applying for citizenship. In the Naturalization Law of 1802, children of naturalized immigrants are automatically granted citizenship provided they are under the age of 21 at the time their parents are naturalized - but the right of naturalization is still limited to free white persons.

But the 14th Amendment in 1867 sharply curtailed Congress’s authority to deny citizenship to those born in the country by declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” Trump and others would like to argue that what the framers of the amendment meant to say - and what the states intended to pass - was that persons born parents with some particular legal status in the US are citizens, while others are not. There is really no room for this interpretation, however - unless we suppose that someone who overstays their visa is somehow outside the ‘jurisdiction’ of the United States, which is unreasonable given the evidence available.

Indeed, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 put this to the test. Wong Kim Ark, born in California to Chinese parents, had left the country and then had been barred a return. The government claimed that he was excluded by the Chinese Exclusion Act, while he claimed to be an American citizen under the 14th Amendment. The landmark 1898 US vs Wong Kim Ark case that followed defended the ideal of birthright citizenship that many conservatives now seek to overturn.

The Wong Kim Ark case concluded that the principle of birthright citizenship had already been upheld by common law and noted “That all children, born within the dominion of the United States, of foreign parents holding no diplomatic office, became citizens at the time of their birth, does not appear to have been contested or doubted until more than 50 years after the adoption of the constitution”; the 14th Amendment, then, merely solidified an understanding that had already existed for some time.

What Wong Kim Ark had to contend with, however, was the relatively new issue of racial restrictions on immigration and the creation of new classes of ‘illegal’ immigrants. However, while the idea of Chinese exclusion was new, the principle of there being certain persons ineligible for citizenship was not at all - indeed, Wong Kim Ark’s parents would never have been eligible for naturalization under the extant naturalization law, that of 1802, which stipulated that “any alien, being a free white person, may be admitted to become a citizen of the United States”.

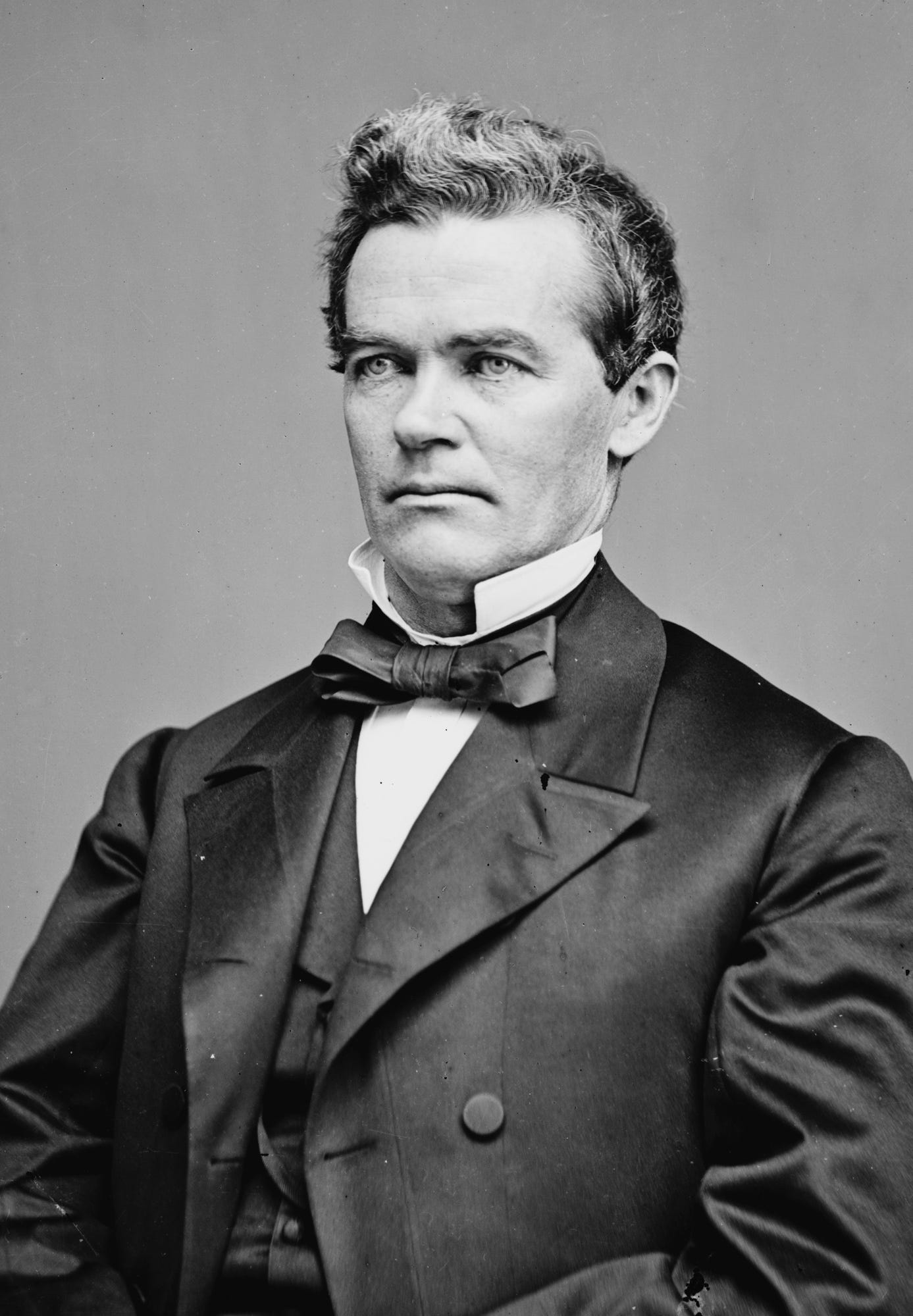

In determining whether Wong Kim Ark was properly decided, critics have tried to emphasize ‘legislative intent’. In the context of 1867, they offer, the focus was on applying rights to formerly enslaved people, and the case being applied to immigrants was not conceived as being within the purview of the amendment. However, the reality - which Justice Horace Gray notes in the Wong Kim Ark decision - was that precisely that debate did arise. During the debate over the ratification of the 14th Amendment in the 39th Congress, it was proposed that the initial clause was unacceptable because it denied states the capacity to deny citizenship either to Chinese or ‘Gypsy’ residents - the unsuitability of both groups described at great length by a Senator Cowan from Pennsylvania. Senator John Conness of California -himself an immigrant from Ireland - replied to this objection that

“The proposition before us, I will say, Mr President, relates simply in that respect to the children begotten of Chinese parents in California, and it is proposed to declare that they shall be citizens. We have declared that by law; now it is proposed to incorporate the same provision in the fundamental instrument of the nation. I am in favor of doing so. I voted for the proposition to declare that children of all parentage whatever, born in California, should be regarded and treated as citizens of the United States, entitled to equal civil rights with other citizens of the United States”

Given this debate and the legislature's decision to adopt the clause, it seems clear that Wong Kim Ark was decided correctly, and to overturn it would be a major break with precedent of a magnitude rarely if ever seen in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The other possible argument, however, that has been brought is that undocumented immigrants as a class of people did not exist at the time of the decision. While Wong Kim Ark’s parents were ineligible for citizenship, they were not illegally in the country at the time he was born. This line of reasoning asserts that being under the jurisdiction of the United States implies legal residence. This is very hard to square with the congressional debate on the matter, however.

The debate immediately following the question of Chinese immigrants makes clear how the congressmen understood jurisdiction; unlike the wording from the original constitution discussing taxation and representation, the 14th Amendment opted not include ‘excluding Indians not taxed”, though it was proposed. Senator Lyman Trumbell of Illinois argued against it, noting of indigenous people living in self-governing communities -

“Does the Government of the United States pretend to take jurisdiction of murders and robberies and other crimes committed by one Indian upon another? Are they subject to our jurisdiction in any just sense. We do not exercise jurisdiction over them. It is only those persons who come completely within our jurisdiction, who are subject to our laws, that we think of making citizens; and there can be no objection to the proposition that such persons should be citizens.”

Others disagreed, arguing that since indigenous tribes were under treaty with the US and followed orders from the military in treaty matters, the phrase ‘Indians not taxed’ needed to be reinserted - though this side lost the debate. The discussion makes clear, however, the jurisdiction was understood by the framers of the amendment to have a very broad meaning. No one doubts the authority of the United States to take jurisdiction over crimes committed by one undocumented immigrant against another, and indeed even in the case of two undocumented immigrants sharing the same citizenship committing crimes against one another on US soil, it is clear that the US has primary jurisdiction over the case.

And finally, while of course not a deciding factor for the courts, it is important to reiterate that the concept of jus soli citizenship is liberal at its core. So long as our system of states requires the assignment of citizenship, it is far more liberal to do so based on the land of one’s nativity rather than blood or status of one’s parents. Automatic citizenship based on the place of birth is an objective measure that reduces the potential for the government to withhold citizenship in ways that are racially or otherwise discriminatory. Moreover, a lack of birthright citizenship would increase the number of undocumented people living in the United States - and thus increase the number of people subject to greater risks of arbitrary mistreatment and denial of rights.

The meaning of the 14th Amendment as regards citizenship is, regardless of what Trump or his supporters argue, clearly settled in the law. Any effort to change that must be resisted not only in the courts, but with the full power of liberal civil society.