Buy (North) American

With the beginning of a new administration, it is natural that the focus is on what changes should be expected - and President Trump's raft of executive orders, often directly overturning those of his predecessor, has certainly strengthened that focus. However, a hostility to trade is a longer-term trend in American politics for the last eight years and one to some extent shared by both Biden and Trump. Trump's campaign rhetoric has long emphasized the need to get the US out of 'bad deals', and in office he managed to renegotiate provisions of 'Nightmare NAFTA' and replacing it with the USMCA. Joe Biden was not as openly hostile to trade with our allies (compared to his willingness to implement punishing tariffs on China), but nonetheless major components of signature bills he signed into law - everything from electric vehicle subsidies to infrastructure spending contains provisions specifying that they are to benefit American producers. Trump's intended tariffs in his second term – reportedly proposing 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada - represent a potentially major escalation of this protectionist philosophy. This hostility to trade flies in the face not just of liberal thought on trade but of sound economic logic. The most common defenses - both economic and strategic - may have some merit when applied to other countries, but mostly fail in their application to Mexico and Canada. Expanding Buy American provisions and free trade policies to North America makes both strategic and economic sense.

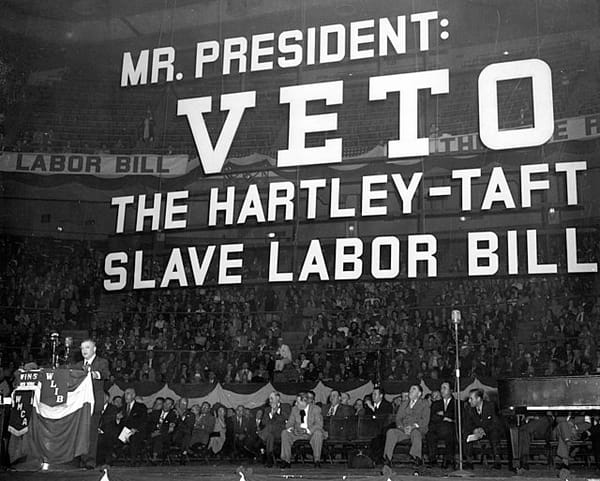

An old debate

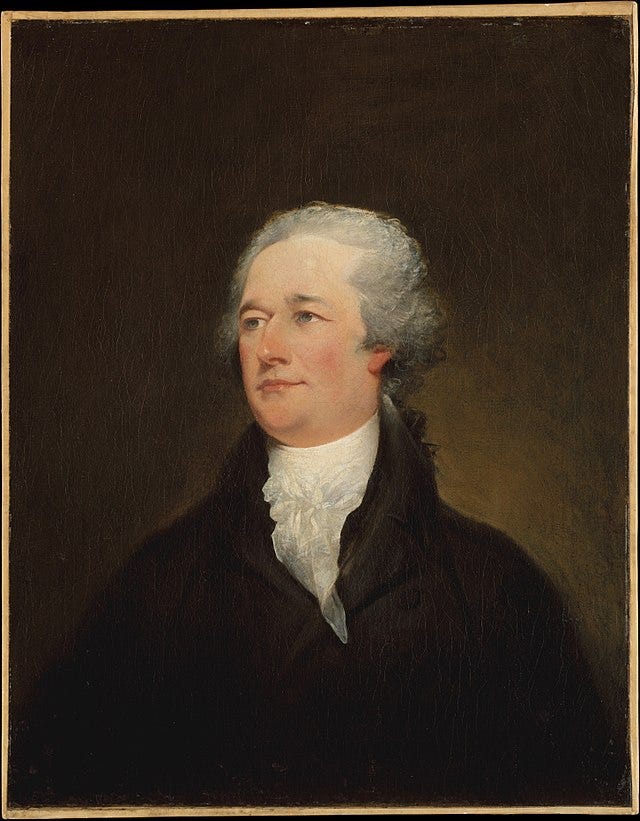

The debate over American trade policy is, of course, as old as America itself. It was an early conflict between Alexander Hamilton’s economic vision and that of Thomas Jefferson; indeed, in his Report on Manufactures, Hamilton gives a useful summary of the key argument against his position:

“If contrary to the natural course of things, an unseasonable and premature spring can be given to certain fabrics, by heavy duties, prohibitions, bounties, or by other forced expedients; this will only be to sacrifice the interests of the community to those of particular classes.

but goes on to justify the need of encouraging manufacturing particularly because other countries had done the same, and the country's economic future required developing an industrial base. The use of tariffs to support home industries grew dramatically in the 1800s and became one of the primary questions of political economy of the era. Proponents of protectionism argued that American 'infant' industries needed assistance in getting started, that it would not do to simply import from Britain or Germany goods that the US should be learning to produce at home. The flaw in this reasoning, Henry George pointed out well in his work Protection or Free trade, asserting that the idea that ‘we should keep our own markets for our own producers’ was akin to the absurd ideas that “We should keep our own appetites for our own cookery, or, We should keep our own transportation for our own legs.” Restricting the market from importing goods, in such a case, was equivalent to robbing a person of their ability to enjoy the cooking over others, or, more dramatically, to avail themselves of a carriage or horse for their transportation. And this has generally been the Liberal position, pursued by Franklin Roosevelt, Bill Clinton, and many in between - lifting restrictions on trade so that American consumers could get cheaper products (and, importantly, so that American producers could get cheaper raw and intermediate goods).

But the benefits of free trade are not always obvious, and not always evenly distributed. This has left it open to critics, especially among industries - and workers therein - perceived as losing out to foreigners. While these movements have generally been out of power in the post-WWII US, since Trump’s successful 2016 campaign both parties have seemed enthusiastic to adopt protectionist policies, especially to prefer American manufacturing. The results have harmed our relations with neighbors and made our investments less efficient.

Hardly a costless provision

Canada, for one, has been understandably annoyed by Buy America provisions and other ‘America first’ policies for years, and with new tariff proposals tied to frightening rhetoric about annexation coming from Trump the potential to create a rupture between the countries is greater than ever. Throwing up trade borders between nearby metropolitan areas such as Seattle and Vancouver or Detroit and Windsor makes little sense, but American policies have put the Canadian government in a difficult position; after all, what government wants to admit that the best path forward is to let their larger neighbor act with impunity? The inability of Canadian or Mexican leaders to show wins for their voters on this topic puts unnecessary strain on these relationships - a dark splotch in a bright relationship with Canada, and further burdens to an already strained relationship with Mexico. Responding in kind, with tariffs on American goods and other economic retaliation, seems a political inevitability.

In addition to diplomatic costs, ‘keeping our own transportation for our own legs’ has gone beyond metaphor and created an impact on our own transportation policy. The provisions have been cited as a factor in rising costs of infrastructure projects, contributing to an already alarmingly poor record of cost control for transit projects in the US. Philip Rosetti, Jacqueline Varas, and Brianna Fernandez at the American Action Forum note that in the case of metro construction, “By refusing to take advantage of established global supply chains for metro cars, U.S. procurements for metro cars are merely paying a premium for the companies to open manufacturing locations within U.S. borders.” Similarly, Robert Atkinson at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation argues that the US IT industry is inadequately prepared to supply the needs of Buy America provisions in the Infrastructure and Jobs Act in an efficient way. And simply by adding another requirement to government procurement, these kind of provisions necessitate hiring more administrative and compliance staff, a cost in itself.

Raising tariffs to Canada and Mexico would put similar burdens on private markets. At a time when the US faces a crisis in housing, tariffs on a prime source of lumber and other construction materials have the potential to exacerbate it. At a time when sea lane security seems more tenuous than it has for decades, tariffs on Mexico threaten access a potentially vital manufacturing partner - and especially substitute for factories located across the Pacific.

Ultimately, American consumers may, and perhaps should, choose on their own to look for a ‘Made in the USA’ label when making purchasing decisions. But when the purchase is made by the government on their behalf, the priority should be delivering the best government services possible - and governments should give consumers the freedom to make these decisions for themselves, based on where they can get the best products to meet their needs.

The arguments for Buy American…

There are, however, arguments that are not perfectly economic in nature that are used to defend these kinds of provisions. To continue George’s metaphor, one reason to save one’s own transportation for one’s own legs is to strengthen the legs in case alternative transportation is suddenly unavailable. This kind of strategic consideration is a common argument in favor of ‘Buy American’ provisions and industrial policy - if American industry doesn’t get support, we’ll be out of luck in the event that we lose access to our trade partners.

There are important examples of this. For example, Taiwan’s massive dominance of the semiconductor industry puts the US in a terrible position if that state is cut off from foreign trade by military intervention or some other event. For this reason, encouraging the development of a domestic industry, via protective tariffs or an indirect subsidy like ‘Buy American’, may be justified.

Moreover, when government spending is used as countercyclical fiscal policy - policy designed to increase demand in the economy during recessions - Buy American might also make sense. Import leakage of stimulus dollars makes the stimulus less effective as fiscal policy and might make major relief spending ineffective. Similarly, seeking the move the balance of trade in a more positive direction can serve to increase aggregate demand, again having an expansionary fiscal effect. In the current economy, facing rising prices due to high levels of demand, these concerns are less pressing, but in a future recession they may become more salient.

…are unconvincing.

However, in the case countries with which the US shares a land border, these arguments make much less sense. Trade with these countries will only potentially suffer from this problem of strategic disruption if direct conflict occurs between them and the US, or extreme unrest makes their industries unreliable. This is exceedingly unlikely with Canada, and the probability is also low with Mexico unless the US executive takes a belligerent turn. Instead, they are more likely than not to be there for the US offering critical support when crises emerge. This was shown during the early months of the COVID pandemic, when Mexican exports of ventilators to the US surged; later, the US would reverse the direction of sales and send ventilators to struggling Mexican hospitals. Even beyond imports and exports, the close connection between the US, Canada, and Mexico was demonstrated as firefighters from all three countries worked together to battle the devastating Los Angeles fires this month. The three will even host the World Cup together in two years.

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a case where the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico are unavailable to American shipping, minus a collapse in American naval power that is on no one’s radar. There are of course questions of not wanting to grow dependent on states that could over time become unfriendly; Nicaragua and Venezuela present examples. But for the NAFTA countries this is not a serious threat.

Moreover, the interconnectedness of the NAFTA economies means the idea of stimulus money ‘leaking’ out of the US is also a lot less concerning than it might be given a different country. US exports to Canada came to over $250 billion in 2021, over 1/8 of Canada’s total GDP; exports to Mexico were roughly the same, thus making up an even greater portion of GDP. To the extent that there is a fiscal multiplier effect to stimulus spending, even spending that is spent in Canada and Mexico is likely to redound into the US economy to some degree - and a multilateral agreement on government procurement and free trade between the three countries, and potentially more, could benefit them all.

Real life is more complex than an economic textbook, and so sometimes the perfectly free trade we might advocate in theory would be detrimental given the realities of business cycles and strategic industries. But this is not sufficient reason to limit trade with our closest neighbors, especially as they are likely to make substantial contributions to the economy as major climate change prevention and adaptation projects are required in the coming decades. Reversing the protectionism that has grown more central to American politics will take time - and probably smart policy to better distribute the gains made from trade. But to the extent that it can be accomplished, free trade, at least on the North American continent, has very few drawbacks relative to the immense positives.