Honoring our ‘incompatible’ ancestors

Today, nobody would doubt the contribution of the Irish to American history, culture, or economics. But as Douglass was writing, the Irish would have appeared every bit the ‘culturally incompatible’ immigrants Vance is warning Germany about.

US Vice President JD Vance recently offered some unsolicited advice to the nation of Germany, suggesting that if the Germans continued allowing in immigrants from countries “totally culturally incompatible with Germany’ then ‘Germany will have killed itself’, and the US wouldn’t be able to save them, as much as Vance proclaimed his love for Germany and the German people.

Leaving aside the discomforting notion that JD Vance loves, as he claims, some notion of the German nation without Germans of non-European descent present (a notion with an obviously fraught history), it’s worth pondering today, when many Americans are observing St Patrick’s Day and celebrating their Irish heritage and that of the nation as a whole.

The celebration of the Irish in America has a long history, even outside of Irish communities themselves: In Frederick Douglass’s ‘Composite Nation’ speech he notes the Irish alongside his own Black American community as crucial to the building of the nation as it existed by the 1860s:

“ It is no disparagement to Americans of English descent, to affirm that much of the wealth, leisure, culture, refinement and civilization of the country are due to the arm of the negro and the muscle of the Irishman.”

Today, nobody would doubt the contribution of the Irish to American history, culture, or economics. But as Douglass was writing, the Irish would have appeared every bit the ‘culturally incompatible’ immigrants Vance is warning Germany about.

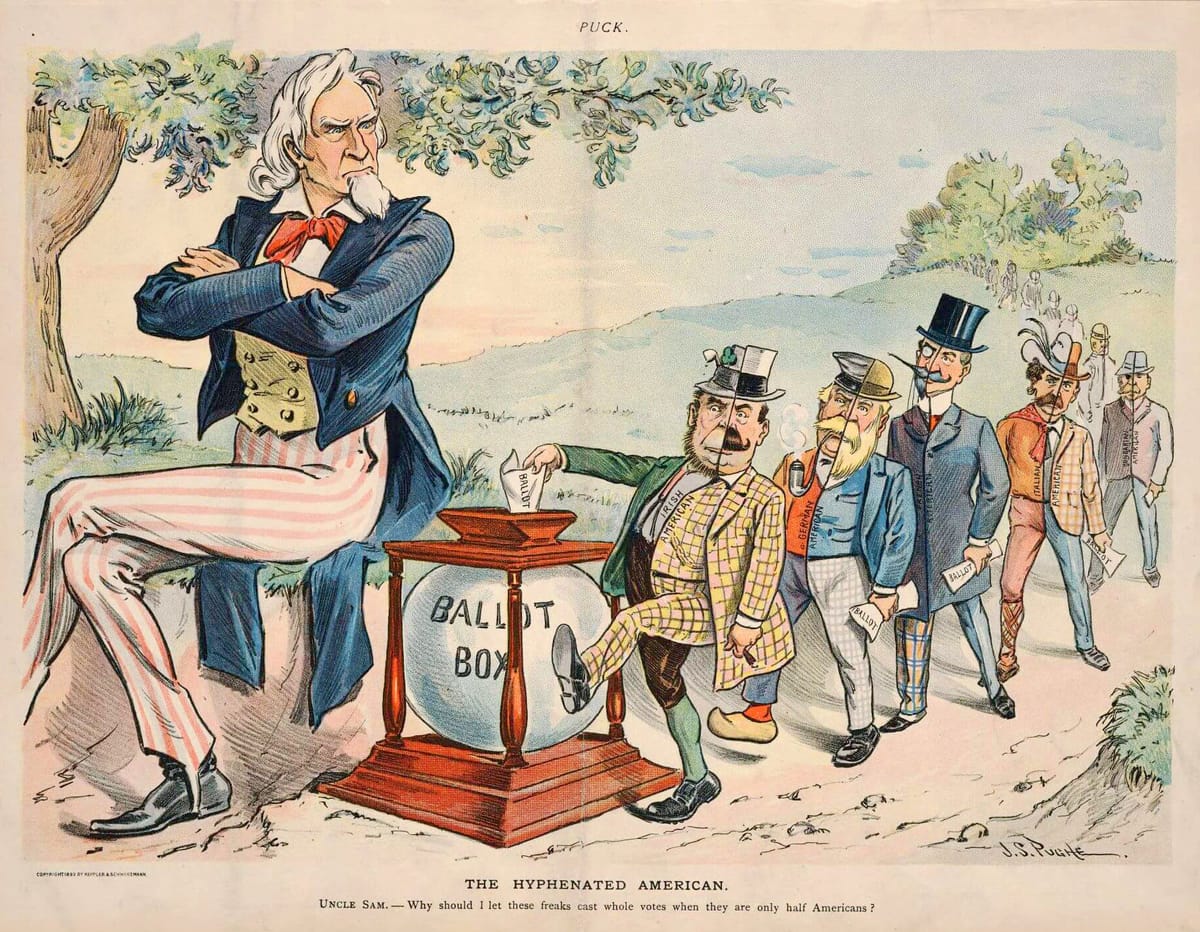

Besides baldfaced eugenicists, those who invoke ‘incompatible cultures’ typically point to immigrants’ minority religions, their supposed clannish behavior and corruption of electoral politics, and their political radicalism (especially their supposed loyalty to socialist or anarchist ideals). The Irish Americans who today are as archetypically ‘American’ as any other group checked all of these boxes when they first arrived to the United States.

While of course most Irish are Christians (in contrast to the Muslim immigrants Vance was almost certainly disparaging in Germany), at the time of their arrival anti-Catholicism was deeply engrained in American culture, and the belief that the Irish would be loyal to the Pope rather than their new country was neither a niche fear nor a completely unfounded one. And the anti-Catholics had a distinguished pedigree in the country: Immediately preceding independence, Alexander Hamilton had referred to ‘arbitrary power and its great engine the Popish Religion’ when denouncing the Quebec Act, and into the 19th century a great many Americans agreed that Catholicism, with its absolute hierarchy and the pope’s monarchical stylings, was incompatible with American institutions.

And these fears were not without foundation - some Irish Americans were indeed disloyal to the United States in favor their coreligionists. Hundreds of Irish Americans deserting the United States and fought alongside Mexico during the Mexican American war; their punishment for treason when captured was one of the largest mass executions in the history of the US. Catholic Irish Americans also fought against Giuseppe Garibaldi (himself a temporary US resident) Italian forces and in favor of the Pope in 1860. Even after the Civil War, a conflict in which many Irish perished in the Union Army and by their sacrifice someone improved the standing of their people in the eyes of other Americans, Irish nationalism complicated US foreign policy. The ‘Fenian Raids’ by Irish Americans into Canada were a diplomatic nightmare. An immigrant group gathering together armed militias numerous enough to invade neighboring states is every bit as destabilizing as anything we’ve seen with Muslim or Eastern European immigrants in Western Europe.

Irish Americans did rapidly assimilate in one regard – they were quick to embrace electoral politics to better their positions. Among the first Congressmen of Irish Catholic descent was John Morrissey, a bare knuckle boxer and reputed gang leader who was just one of many Irish-American politicians to engage in ethnic machine politics in arrangements so openly corrupt that they make the urban legends Nativists tell about immigrant corruption sound demure by comparison. And Irish Americans were politically influential, in quite radical (if sometimes opposing) directions: both Senator John Conness, one of the driving forces behind the birthright citizenship provisions in the 14th Amendment, and Denis Kearny, among the most influential activists *against* Chinese immigration, were born in Ireland. Among the most important radical organizations of the 1800s were the Knights of Labor, which in the late 1800s was lead by a son of Irish immigrants, Terence Powderly.

In other words, the Irish did not wait some number of decades to dive into US politics or begin lobbying for their interests or even for radical causes. Indeed, the immediate impact of Irish immigrants on US politics was if anything more pronounced than that of almost any group of immigrants in the western world today. This was in spite of the religious and nationalistic sentiments that, both frequently in the imaginations of their detractors and periodically in actual fact, competed with their loyalties to the United States.

And yet few would say that in accepting the Irish the United States ‘killed itself’ – indeed, it’s hard to imagine the United States in the absence of the Irish-descended community, a fact we celebrate today. Whatever complications they brought to 19th century American life were more than compensated for by their immense contributions – economically, politically, and culturally. The same will almost certainly be true of numerous immigrant groups now dismissed as ‘incompatible’ – one can only imagine the cultural events that will be held in the future by their descendants celebrating their heritage they will have built and the unique contributions they will have made to the countries they are today choosing to make home.