Tariffs are neither fair nor simple

Tariffs appear simple because they are baked into prices, but behind the scenes is a complicated, regressive system ripe for corruption

Although it is overall among his most incoherent policies, Donald Trump’s proposed 10% tariff appears to be polling surprisingly well among voters - 56% of voters support it according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll a few days ago. Breaking that support is a key element of breaking conservatives’ reputation on the economy, one of a few issues where liberals typically score poorly in US opinion polls.

One reason it may be popular is that Trump continues to tout it as a panacea for any number of issues - after all, the tariff is supposed to replace taxes on tips, overtime, and social security, while also paying for childcare and, rather counter intuitively even for Trump, lowering grocery costs.

But this approach runs headlong into a other voter priorities - that taxation be fair, and that it be simple. Adam Smith declared of taxes that “subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state.” The idea can be variously interpreted, but in its most general formulation Americans tend to support it - taxes should be paid by those who can afford them, and also it’s fair that some people pay more than others because income and property are secured only through government action. Taking this sentiment a little further we get to Henry George supporting land value taxes specifically, because of all kinds of property land has its value only if it protected by a government. The New Deal progressive income tax was largely justified because, again, highest earners are those who would suffer the greatest material fall without the security provided by the state. In any event, a shift towards tariffs cannot be justified on these grounds.

Perhaps we could declare that overseas trade requires the maintenance of a navy and thus a tariff on such trade to support the navy is especially justified, but trade with our top trading partners - Canada and Mexico - predates the establishment of the Constitution and is if anything impeded by government actions. A tariff on automobile parts or softwoods does not seem to have be at all in proportion to ‘revenue….enjoyed under the protection the state’, certainly not compared to capital gains secured only through the property rights and banking system provided by the state. Here, Harris’s taxation plans seem far more fair.

Moreover, if we consider ability to pay as a good criterion for taxation, tariffs also fall. There are many imported goods that Americans currently enjoy which would be out of reach if tariffs drove up their prices. Homes, automobiles, apparel, and electronics are all available to the working class at more affordable prices because materials and goods can be sourced from overseas. Even if people of all incomes spent an equal portion of income on imported goods (unlikely, since we know lower income individuals consumer a greater portion of their income), a consumption tax like this is unfair to those with the least property. Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations that “Where there is no property, or at least none that exceeds the value of two or three days' labour, civil government is not so necessary.” It would seem that, thus, those individuals with only a few days’ worth of property are those who need the government least, and thus should be sacrificing the least for its support. But driving consumers to higher priced American goods (and they will be higher priced as their competitors are squeezed, even if they are not now) will push those sacrifices precisely on these families.

Finally, Americans claim to value simplicity. Large majorities consistently tell pollsters that their taxes are too complicated, though they don’t necessarily want to give up deductions and credits to simplify them. In this sense, a shift from an income tax to a flat tariff would at least make taxes simpler. But this is unlikely, of course, to happen. First, Trump has promised to introduce all kinds of new complications to income taxes - by treating tips and overtime separately in the tax code, for example. More importantly, though, tariffs are almost never simple. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff is instructive here: though intended as a broad protective tariff, it includes an extensive list of ‘free goods’ untaxed, such as (to look at only a section)

PAR. 1751. Rennet, raw or prepared.

PAR. 1752. Patna rice cleaned for use in the manufacture of canned soups.

PAR. 1753. Sago, crude, and sago flour.

PAR. 1754. Santonin, and salts of

PAR. 1755. Sausage casings, intestines, bladders

PAR. 1757. Cowpeas not specially provided for, and sugar beet

PAB. 1758. Selenium, and salts of selenium

PAR. 1759. Sheep dip

PAR. 1760. Shingles of wood.

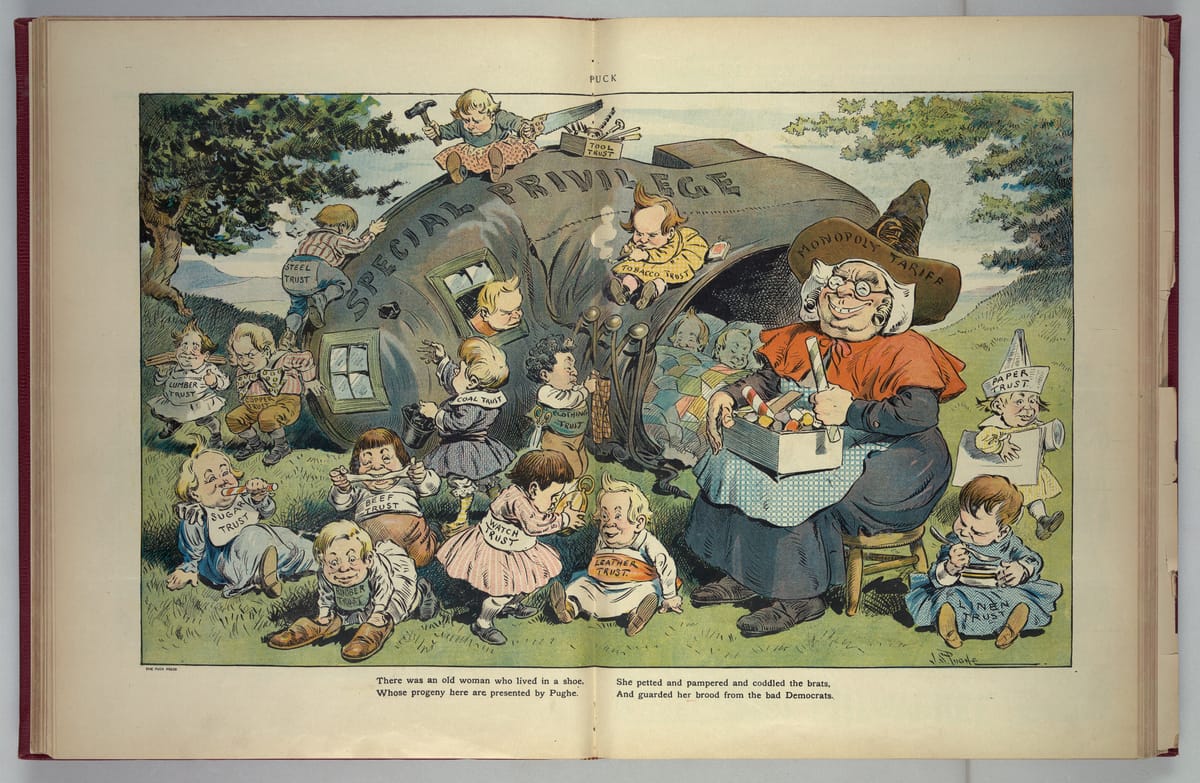

How did this list get selected? There may be a national interest logic to many of these goods, but it is easy to imagine the scramble for exemptions that major trusts and their lobbyists in congress would undergo every time a new tariff bill was up for consideration, and almost impossible to imagine a bill getting through today’s congress without the same. There is a reason progressive tariff reformers denounced the tariff as ‘the mother of trusts’ - establishing monopoly power in the US was much easier with a friendly congress, able to tariff your international competitors out while protecting your international suppliers. Far from draining the swamp, establishing a tariff regime creates many more opportunities for patronage and corruption - which Americans would quickly realize once the tariff schedules were released.

So what is to be done? I don’t think there is any way around the mass (and speedy!) education of the electorate. As Henry George notes in Protection or Free Trade, a public that understands basic economics is not optional in a democracy - “with matters which relate to the production and distribution of wealth, and which thus directly affect the comfort and livelihood of men…intelligence which can alone safely guide in these matters must be the intelligence of the masses, for as to such things it is the common opinion, and not the opinion of the learned few, that finds expression in legislation.” This seems a high charge indeed when much of the public seems stubbornly resistant to new information.

It has, however, been done before. When George was writing, his books were bestsellers and commonly read in union halls and other gathering places. A true mass movement was required to get the votes necessary to implement a constitutional amendment allowing for income taxes, largely for the purpose of giving Congress the flexibility to lower tariffs. Such a movement isn’t going to be built in forty some days. But very simple education about what tariffs are - delivered by trusted elements of civil society like union, senior organizations, and yes, formal economics courses - can help deliver enough information to cut into Americans’ apparently high baseline support for tariffs. This can be especially effective when focused on these key points:

-Tariffs do not tax the rich more; they almost certainly will require greater sacrifices by the working class

-Tariffs are not based on ability to pay; instead, they will force lower income earner to forgo purchases just like any tax would

-Tariffs may appear simple because they are baked into prices, but behind the scenes is a fiendishly complicated system ripe for corruption

Ensuring that most Americans receive this message should be one of the key goals of liberal messaging and should be undertaken by anyone with an understanding of basic economics and a platform.