Thoughts on the traditions of Lent

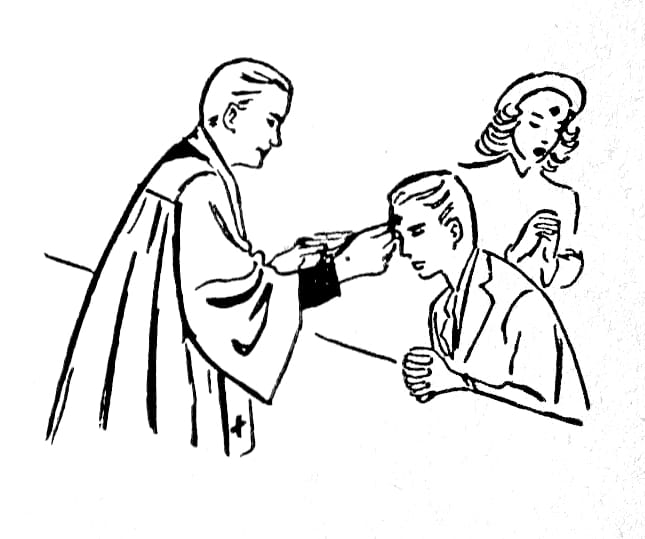

Perhaps ironically, given the devotion of this newsletter to Liberalism, I find myself thinking a great deal about tradition and what - at its best - it can offer, in times of crisis perhaps more than ever. And as I write, the most salient tradition is that of Ash Wednesday, observed by the Catholic and many Protestant churches as the beginning of the Lenten liturgical season. Two Lenten themes strike me as being particularly relevant in our day - the recognition of mortality and the beginning of a season of fasting.

For Christians, of course, earthly 'mortality' is a theme primarily emphasized to highlight the contrast between this life and the next, which in Christianity is one free of mortality and thus superior in quality and importance to this one. However, mortality is thus far universal, and despite the hopes of our most ardent futurists probably will be for some time. Pausing to consider this fact - "You are dust, and to dust you shall return" - can and should provoke more than just spiritual resignation. Humans are mortal, and every bit of our bodies will be returned to the universe to be reused. Some may seek immortality in genetics - the copying of their genetic material into a new organism serving the same purpose as reincarnation does in other religions - but to my mind this is a bit of a false promise. Biological offspring are not simply extensions of their parents, and treating them as a path to genetic immortality makes it harder to respect their individual potential and development.

Instead, the remembrance that we will die should, in my view, lead our minds to higher things even in this world. 'Creating a legacy' doesn't lend one immortality any more than having children, but devoting more time and energy to the future - be it the environment, educating future generations, or contributing to the structures that allow human freedom - is an appropriate response to the understanding that we all will depart the physical realm. The worldly comforts and luxuries that may call out to us should perhaps seem a bit more trivial by comparison when we remember the reality of ashes and dust.

And the question of luxury leads also into another theme of Lent - the fast. The traditions around fasting during Lent (or any other time) are myriad, complex, and somewhat dynamic, but the general thrust of the Lenten fast is to put off the most 'decadent' foods - rich foods like meats, dairy, and the like, alongside absolute fasts that have long been central to the ascetic traditions of Christianity (and many, perhaps most, other religions).

This might take on a new depth, however, when one considers what the economies of the societies observing the traditional Lenten fast were like. The overwhelming majority of economic activity was aimed at allowing the consumption agricultural goods; cutting out 'luxurious' foods was indeed cutting most 'excess' consumption from society. In a time of economic and especially ecological uncertainty, there is an important lesson here besides simply dietary restriction (though adopting a vegan diet, as traditionally required through Lent in many churches, certainly seems appropriate in light of the environmental degradation associated with animal products). How much every day consumption is supporting organizations or regimes characterized by human oppression? How much is redirecting income from worthy causes abroad and at home?

'Simply lifestyle changes' are often proposed as a substitute for policy reform, and have, sometimes rightly, been accused of distracting from it. But the reality is that the current lifestyles of many hundreds of millions of people in the developed world are simply unsustainable. If policy is not going to shift to make that less the case - and it's not looking likely at least for the next few years - voluntary renunciation, or at least moderation, of luxuries like fossil fuels and meat products may be the best substitute available today. And if doing so also frees up income for charity or aid, so much the better - it is no coincidence that in the Gospel of Matthew, the instructions for fasting, prayer, charity, and 'laying up treasure in heaven' are all in the same chapter.

I hope the world is not truly in as dire of a condition as it appears to me today, and that in hindsight we are simply in a troubled season. But whether the crises we're facing today, with a hot war in Ukraine and occupation in the Middle East, with economic and social tensions both within and between formerly friendly states, are of limited duration or become the new norm, the tradition associated with Lent have much to offer even those who don't subscribe to their spiritual significance.