What if the New Deal Coalition...wasn't?

One of the great ‘true but misleading’ statements of 20th century American politics is that ‘more Democrats than Republicans voted against the Civil Rights Act”; one of the greater oversimplifications in response is the claim that the parties ‘flipped’ somewhere between the 1940s and 1970s. The electoral record is indeed complex, particularly as Southerners showed some apparent sectional loyalty by embracing Nixon over the Minnesotan Hubert Humphrey, but largely coming back to the Democratic fold for one vote for Georgian Carter and giving Arkansas Clinton relatively good results as well. This irregular voting behavior has opened the door for some outlandish theories - that it was, for example, primarily due to changing economic factors unrelated to the Civil Rights movement.

The question of the New Deal coalition also has relevance by analogy to debates today - for example, if the Democrats really want to build a 'Big Tent' like before, voices like Ezra Klein, David Shor, and Matt Yglesias have suggested compromise on 'culture war issues', akin to Democrats' compromise on Civil Rights in order to push through the New Deal. From this point of view, ejecting from the party those who have illiberal views on social issues threatens the strictly economic ones where Democrats may be more popular - things like raising the minimum wage, for example.

But what much of both sides of the discussion misses is that at least since the death of Franklin Roosevelt the South has not been a clear coalition partner even in the economic issues that are ostensibly the foundation of the ‘New Deal Coalition". Well before the 'neoliberal turn' of the Democratic party and even before the last Civil Rights acts were signed, the coalition between Northern and Southern Democrats was uneasy. Simply looking at votes on two issues - the Taft Hartley Act of 1947, and the Social Security Amendments of 1965 - reveals that the ‘coalition’ was always on shaky ground and the vision of white southerners as reacting *against* a neoliberal turn by the Democrats doesn’t make much sense - and the reality is that even if they had remained formally within a party that was willing to compromise on segregation, they were unlikely to deliver reliable votes.

Taft-Hartley and the De-Unionization of America

One of the keys to producing the New Deal coalition and the compression of wages that typified mid-century American prosperity was the rise of unions. This trend began during the Depression and accelerated as New Deal programs increased the bargaining and organizing rights of unions. However, after World War II and with the beginning of the Cold War, serious challenges to this invigorated union movement started to pick up steam.

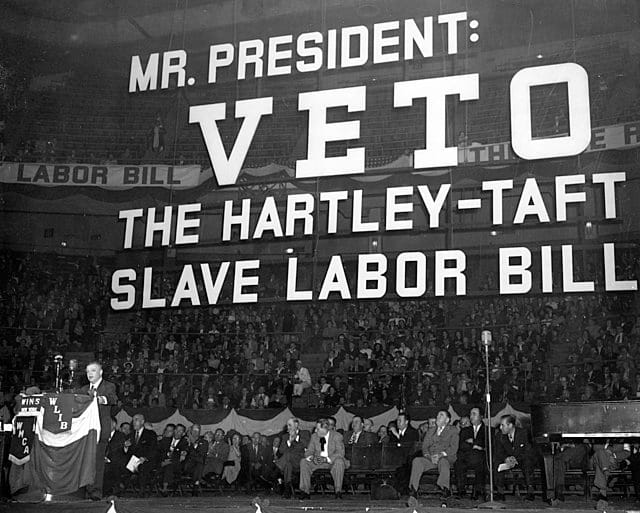

The Taft Hartley Act of 1947 outlawed labor tactics like solidarity strikes and the maintenance of closed shops. It was vehemently opposed by President Truman, but became law over his veto because of its overwhelming, bipartisan support in Congress. The fact that Democrats, who had leaned so heavily on organized labor under Roosevelt, could make this strategic miscalculation is easy to chalk up to Cold War paranoia about socialist workers’ unions. But the regional divide gets at something perhaps more interesting.

Overcoming Truman’s veto required Senators from both parties, as the Republicans in 1947 had only a small majority - 51-44. However, Democrats split on the act, allowing the bill to become law despite the president’s opposition. The regional divide, however, is important. Of the Senators representing the former Confederacy, all 21 were Democrats (there was only one Senator from Mississippi at the time). Of those, one did not vote and only three voted against the Act. The remaining 17 formed a pivotal group that allowed for this restriction on unions, which Truman had denounced as “a shocking piece of legislation…unfair to the working people of this country”.

This was of course only one of many disappointments Truman faced from his ‘partners’ among the Southern Democrats, but it is among the most notable because it would have long term implications on the strength of organized labor in the country. It also occurred before the 1948 executive order desegregating the military, indicating that it was not a revolt against Truman’s integration policies but rather an independent expression of conservative opposition to union activity. The states of the Confederacy - or at least their voters at the time - did not seem to harbor any particular interest in the left leaning ‘Fair Deal’ Truman was pushing.

There are a couple possible reasons for this. One is that the union movement and the kind of solidarity it proposed was seen as a threat to the racial political economy of the south even if it was not explicitly framed in those terms. Another is that, given the extremely low turnout in Southern elections, even among whites, the political class of the South was largely separate from the working class that might have stood to benefit, while it was socially and politically intertwined with the class of business owners opposed. Whatever the reasons, however, it seems unlikely that any amount of social compromise was going to win this pivotal block over. In the end, once the catastrophe of the Depression and the crisis of war had passed, the 'Solid South' was in fact a bruised reed Truman could not rely on even for his largest priorities.

The Great Society and its Opponents

Further evidence comes from the Great Society, championed by (Texan) president Lyndon B Johnson. Unlike Truman, Johnson was known for his ability to get good results from congress, helped along both by his own adeptness at ‘playing’ various members as well as the enormous majorities he held. The amendments made to the Social Security Act in 1965 created key parts of Johnson’s 'great Society Program - Medicare and Medicaid. These programs today form the greatest part of American government healthcare spending. Since Medicaid especially is designed to benefit low-income families, and the South suffered from lower incomes generally than the North and Midwest in the 1960s, one would expect this expansion of the safety net to be particularly popular there.

This expectation does not perfectly match reality, however. Overall, the act passed resoundingly, with a large majority of Democrats voting for it and Republicans split roughly in half. However, of the 7 Democrats voting against the act in the Senate, 6 were from former Confederate states (and the seventh was from Oklahoma). This still means that a majority of the 20 Democrats from ex-Confederate states voted in favor (Strom Thurmond had a this point already switched parties, and John Tower from Texas had been elected as a Republican - both also voted against the bill). However, it’s a much lower rate of support than among Northern Democrats, and indeed only a bit better than Republicans.

Complicating the twentieth century ‘Democratic coalition’

Why is this worth a review? Well, if Democrats are seeking a ‘Green New Deal’ or a new Civil Rights act, it helps to know how those things were accomplished in the first place. And the answer is - not with party unanimity. Even in areas well outside the question of civil rights, major swaths of the Democratic party were never committed to the goals of Democratic presidents. Party polarization has increased enormously since then, of course, and so the same level of cross aisle voting is unlikely. Nonetheless, understanding its importance in previous eras can help us at least understand the peculiarity of our own.

It is also important to understand why the Democratic party lost the enormous majorities it once had. It was not due entirely to the Civil Rights movement - though that certainly contributed - but neither was it due to some ‘neoliberal’ drift in the party. Even on economic issues, the Democratic ‘coalition’ always included anti-Labor and anti-welfare elected officials. There is a certain Romantic attachment to the idea that white working-class Southerners form an aquifer of proletarian sentiment waiting to be tapped into, if Democrats were only willing to abandon the deregulation and free trade policies of the last thirty years. But there’s little evidence of this - Southern Senators have consistently been among the most skeptical of unions and of social welfare even when nominally in the Democratic party. Moreover, if more welfare and stronger unions were necessary components to saving the Democratic base among white Southerners, as has been suggested, it would almost certainly have to have happened over the objection of many Southern politicians who presumably understood their electorates rather well - no mean feat, even if it had been a priority.

There are limitations, of course. For one thing, I’ve defined the South to specifically include the former Confederacy, a definition which has the benefit of technical clarity but may not be the most accurate. West Virginia and Kentucky, for example, present a somewhat different story than the deeper South - both were somewhat more amenable to the New Deal coalitional priorities, and both have swung far against the Democrats, at least partially because they have fewer Black voters to make up for the massive party shift of white ones. There were also many more votes than these two, and coalitions at this time were constantly shifting - certainly Southern Democrats could at times be brought on side when a bill needed to be passed that went against their conservative instincts but promised to benefit their constituents. My point is simply that the voting records on key economic policies indicate these were not as common as we might imagine.

None of this is to say the South, or any region, is destined to hold a particular set of views forever. For one thing, Democrats from the South now, especially House members from districts with many Black voters, do often have the kind of social democratic values we associate with the Fair Deal and Great Society. But the story of losing a New Deal coalition over Civil Rights or other social issues is a simplification at least as crude as the idea of the parties just ‘flipping’ midcentury. Even when it seems counterproductive, economic conservatism is an influential ideology that is not always a response simply to material conditions. While Civil Rights and, later, guns and abortion may have made Democrats less viable in these states, these issues merely deepened a division between factions of the party that had surfaced even in economic issues as early as the immediate post war era. And strategists who imagine that strategically dropping liberal positions on trans rights, immigration, or other social issues will allow Democrats to ride a wave of thus far dammed up economic New Deal-ism are likely to end up being disappointed.